Four years ago, I led a small group of people up a stairway cut into the slope of a river canyon. We arrived at the platform overlooking Englebright Dam – a 70-year old, 240-ft-high dam on the Yuba River in Northern California – which is a complete barrier to one of the last wild runs of salmon in the whole greater San Francisco Bay and Delta watershed.

From this perch above the dam, we discussed the dam’s history, its impacts and the steps we were taking to get Englebright decommissioned. The elder in our group spoke up. An avid flyfisher, Yvon Chouinard has spent time on more rivers than I’ll likely ever encounter. I wasn’t taking notes, but the message I took away was: “don’t underestimate the regenerative power of rivers; in the end they will outlast any concrete and steel dam wall.”

This small group of river defenders was well aware of the trends in the US – over 700 dams have been removed in the last 30 years, including some of the largest in recent years. But the story of river revival, we declared that day, needed to find expression through a captivating film that brings to life the transformations that dam removal can inspire.

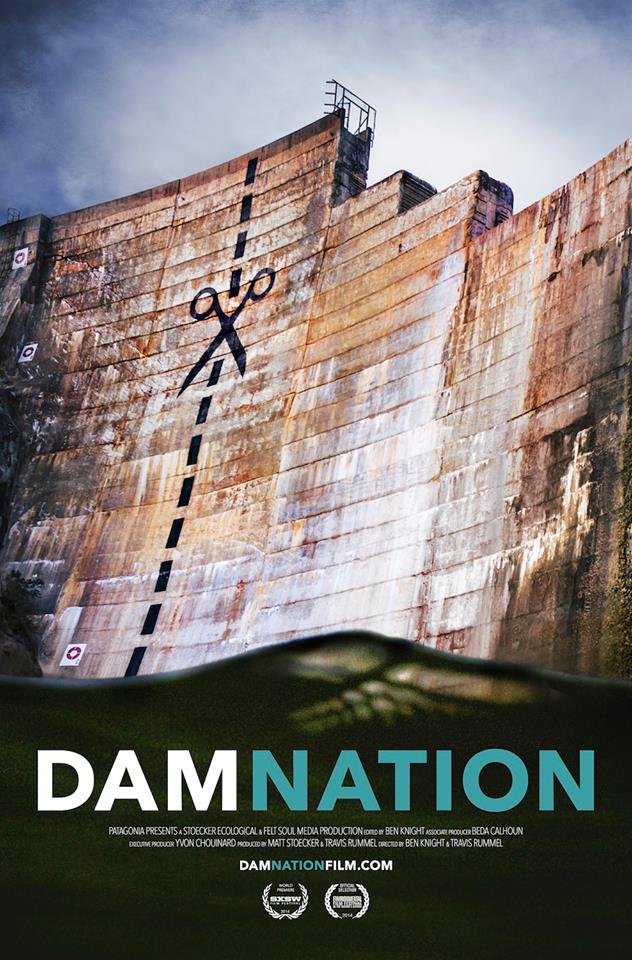

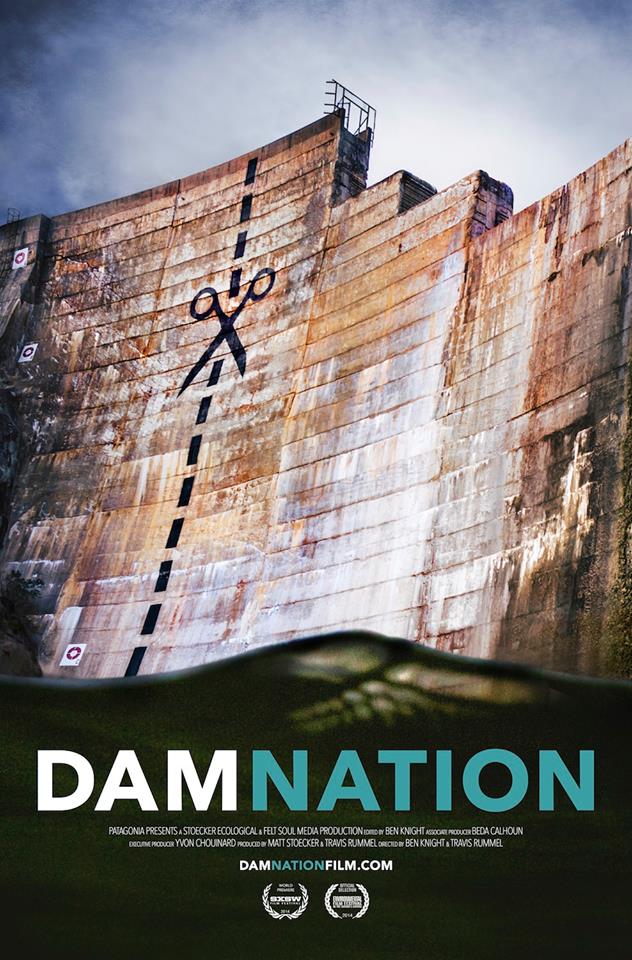

Fast forward to early 2014 when DamNation – the film that was given breath on the Yuba River four years ago – premiered in the United States, winning audience awards at the acclaimed South by Southwest (SXSW) Festival. And while DamNation is a film chronicling the dam removal movement in the US, dams are also being decommissioned in Spain, France and Japan in order to reconnect severed rivers and communities.

Yet while several countries around the world are decommissioning big dams, many others are on a very different course, sinking huge investments into destructive dams. DamNation provokes several questions and provides many lessons.

First, dams have a life-cycle and lose their value over time. Whether built as an electrical plant, a reservoir pool for irrigated agriculture, or an engineered structure in a flood management plan, the physical processes of sedimentation, evaporation and changing precipitation diminish a dam’s ability to perform to its built specifications. Over time, the costs of maintaining dams can out-weigh their economic benefits.

Second, when society’s values and priorities change, dams can stand in the way. 50 were removed in 2013 alone. Many decisions that lead to dam removal in the US are borne out of a new type of balance sheet: when the benefits of revived fisheries, enhanced recreation and respecting the rights and aspirations of indigenous people are factored in, the value of an old dam can’t compete economically.

Third, even when there is broad agreement to remove a dam, it is expensive to safely and effectively decommission a deadbeat dam.

Seventy years ago – when mining interests pushed through the approval of a federal dam on the Yuba River – no one was planning for the long term, nor accounting for the costs of decommissioning. Yet today, with thousands of large dams proposed and under construction throughout Latin America, Africa and Asia, several questions remain unanswered, including:

- Should those who will profit from the hydroelectricity be held liable for the costs of decommissioning the dam at the end of its useful life?

- If these “full life-cycle” costs were properly accounted for in the initial cost-benefit analysis, how many of these new hydro-dams would still be considered economical?

All too often in today’s world, foreign corporations win contracts to build and operate hydroelectric dams, often financed by public funds in the name of “development” of the host country. After a 20- or 30-year period of operating a dam – and garnering profits from the sale of electricity – the corporation will “transfer” ownership of the project to the host government. This is viewed as a “gift,” but the story of big dams that has played out in the US illustrates that this transfer is laden with a host of liabilities, including the eventual costs of decommissioning – or abandonment of an economically unviable dam.

The story in DamNation is from the US, but the lessons and subsequent questions are relevant to emergent economies – will countries continue to invest their future in infrastructure that will have immediate negative social and environmental impacts and eventually create more deadbeat dams? Or will they find a new and sustainable model of development that honors our precious rivers, respects the rights of the people who depend on them, and uses a democratic model of decision-making for our collective future?

More information

International Rivers will be hosting screenings of DamNation in Berkeley on Thursday, June 19 and will also be premiering the film in South Africa in August.